Way back in 2014, we wrote a post about Maya Angelou and Toni Morrison, making it the second of close to eighty literary friendships that we have featured on Something Rhymed. Some time afterwards, our friend Sarah Moore suggested that we write a piece that focused on another of Angelou’s fascinating relationships with a fellow writer …

- Hons And Rebels Review

- Hons And Rebels Jessica Mitford Pdf

- Hons And Rebels Pdf

- Hons And Rebels By Jessica Mitford

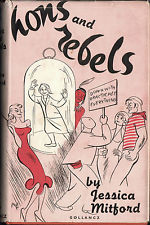

Jessica Mitford, the great muckraking journalist, was part of a legendary English aristocratic family. Her sisters included Nancy, doyenne of the 1920s London smart set and a noted novelist and biographer. Hons and Rebels is a memoir that shocks and amuses by its sheer bravado, a remarkable portrait of an eccentric family by one of its most eccentric members. ‘More than an extremely amusing autobiography. She has evoked a whole generation.’. Hons and Rebels is the hugely entertaining tale of Mitford's upbringing, which was, as she dryly remarks, 'not exactly conventional. Debo spent silent hours in the chicken house learning to do an exact imitation of the look of pained concentration that comes over a hen's face when it is laying an egg.

By the time Maya Angelou and Jessica Mitford met in the late 1960s, both had come a long way from the very different worlds of their childhoods.

Hons and rebels by Jessica Mitford. Publication date 1996 Topics Mitford, Jessica - Childhood and youth., Mitford family, Upper class families - England., Sisters.

Mitford, the fifth of the six legendary Mitford sisters, was born into an English aristocratic family during the First World War. She spent her early years living a life of material privilege in what she would later refer to as a ‘time-proofed corner of the world’.

Angelou’s youth, in contrast, in the American South, introduced her early to racial prejudice and physical trauma. At the age of eight, in the mid-1930s, she was raped by her mother’s boyfriend. In the aftermath of the attack, Angelou became mute – except with her brother – for close to five years.

Angelou and Mitford would come face to face for the first time some three decades later, at the London home of editor and archivist Sonia Orwell, the widow of George Orwell. Angelou, who was around forty, had just completed the manuscript for I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings – the first of her celebrated autobiographies. As such, she was keen to seek the advice of Mitford, a writer herself by then and author of the memoir, Hons and Rebels. First published in 1960, Mitford’s book explored the upper-class upbringing she had fled, the evolution of her left-wing politics and her later life in the United States, where she became a prominent campaigner and journalist.

When Mitford began reading Angelou’s manuscript at the breakfast table one morning, she found it ‘so fascinating’ that she ‘kept reading it all night’. In the years to come, Angelou would be equally effusive about her new friend’s writing, declaring that while reading The Trial of Dr. Spock – about the famous paediatrician’s trial for anti-war activities – she ‘couldn’t put it down’. Soft for mac os x.

In addition to their literary bond, the pair grew close thanks to a shared dedication to challenging social injustices through their writings – a preoccupation, too, of their letters to each other. Such missives also explore their thoughts on political and cultural figures, past and present, and touch on key moments in twentieth century history. In 1992, when Angelou was ‘agonizing’ over the poem she’d committed to write for Bill Clinton’s inauguration and struggling to find her flow, Mitford sent some encouraging advice on possible ways in which her friend might find her ‘unique Maya rhythm’ once again.

By this stage, the pair had grown so attached that, when asked in a 1983 interview for Essence magazine whether black women could consider white women their sisters, it was this particular friendship that came to Angelou’s mind. In answer to writer Stephanie Stokes Oliver’s question, Angelou replied: ‘Jessica Mitford is a sister of mine. If I had to go into a room with a leopard, I wouldn’t hesitate to ask for her.’

In addition to this fierce shared loyalty, there was a lighter side to their relationship. Music was a mutual passion, and one that would lead to an unlikely episode in their later years when Angelou and Mitford recorded a duet of the comic song ‘Right Said Fred’. It would subsequently be included in the charity album Stranger than Fiction, which featured vocal recordings by well-known writers, with proceeds going to organisations promoting literature and literacy.

Singing with Angelou would also play a poignant part in the final stage of Mitford’s life. After being diagnosed with lung cancer in 1996, Mitford’s health deteriorated rapidly. Although she had at first expressed a determination to undergo intensive treatment to prolong her life, in order to keep working on the current book she was writing, the seventy-eight-year-old eventually changed her mind and asked to come home from hospital to die in the company of her family and closest friends.

Angelou visited Mitford on each one of those four precious last days. As Mitford’s husband, the civil rights lawyer Robert Treuhaft would remember it, she was, in some ways, ‘the real doctor’ his wife needed at the end of her life.

He would look back on the sight of Angelou standing beside her friend’s bed and singing songs to her. Mitford was so weak by then that at first she didn’t react. But as Angelou persisted, Mitford would at last recognise who it was and even open her mouth to try to join in. A witness to this long goodbye between two old friends, Treuhaft would fondly recall that his wife’s final words ‘were really songs that Maya started her singing’.

Later, he would say that experience was one of the most profound of his life – a moment when he learned ‘what true sisterhood is all about’ .

Install mac app store for free. What we’ve been up to this month:

Emily has been reviewing edits for her forthcoming book,Out of the Shadows: Six Visionary Victorian Women in Search of a Public Voice, which will be published by Counterpoint Press in North America in May 2021.

In addition to focusing on her own writing, in her role as Director of the Ruppin Agency Writers’ Studio, Emma has been preparing for this upcoming deadline (more information here):

“Base Fortune, now I see, that in thy wheel

There is a point, to which when men aspire,

They tumble headlong down: that point I touch’d,

And, seeing there was no place to mount up higher,

Why should I grieve at my declining fall?—

Farewell, fair queen; weep not for Mortimer,

That scorns the world, and, as a traveller,

Hons And Rebels Review

Goes to discover countries yet unknown.”

Hons And Rebels Jessica Mitford Pdf

- Act V, Scene VI, Edward II by Christopher Marlowe

With these last words, the avaricious Mortimer—seducer of queens and murderer of kings—leaves the stage for the last time—at least as an intact whole. He appears again in the next few minutes, this time in the style of Holofernes, that is, a head sans body. Such is the macabre fate of most of the characters from Sport For Jove’s grisly, yet endlessly compelling and compulsively watchable adaptation of Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II. Scratch download for mac os x.

Seeing a play in which you have no idea what’s going to happen—or even, much knowledge of the author and his oeuvre—often makes for an exciting, engrossing experience. On the other hand, such a play makes it rather hard to review—or at least, review with any modicum of authority. On the subject of Christopher Marlowe, I must confess that I am woefully ignorant. My two points of references are quite shameful: one, the fact that the once-beautiful, now melty-face, Rupert Everett played a version of Marlowe in Tom Stoppard’s Shakespeare in Love, the other, the fact that it was Marlowe who wrote those immortal words concerning Helen of Troy and her maritime-propelling countenance.

Hons And Rebels Pdf

“Tarantino-esque” was how my friend described Marlowe’s plays as the house lights began to dim. Even with that warning, I don’t think I was quite prepared for the gruesome ending that meets Edward, his lovers and his enemies. In terms of Shakespearean equivalents, this is Titus Andronicus territory, rather than Hamlet.

The time is today, or perhaps, the seemingly halcyon period before the turn of the 21st century, if the ever-present double-breasted suit means anything significant. The old king has died, and Edward II is now regent. No-one is more joyful than the king’s favourite, Piers Galveston. Banished from the courts during the time when Edward was merely incumbent regent, Galveston expects great things from his intimate relationship with the king—much to the dismay of the general English nobility, whose world order and innate sense of authority is threatened by Galveston’s very presence. For Galveston’s relationship with the King is unnatural in every sense of the word. Not only does Edward II conceive a great passion for the Frenchman, beyond any trifling, schoolboy infatuation, Galveston is a commoner—a swaggering upstart with dangerous designs above his station. In earlier productions of Edward II, the sexual relationship between the King and Galveston is generally subtext, slyly suggested in the way that Antonio and Bassanio’s friendship in The Merchant of Venice can be seen as more than platonic. In Sport For Jove’s production this great, grand passion is not merely subtext, it is the text. For the King’s love for Galveston is all-consuming: grandly, mythically romantic to the extent that Paris’ was for Helen of Troy. Like the fates of their literary predecessors, the love shared between Edward and Galveston is riotously destructive, shattering every bond, every vow of fealty, by the court to the king in its wake. What happens next is civil war as bloody as anything that Homer could have conceived, with the spurned Queen Isabella, the dastardly Mortimer and the French imperial forces a united bulwark against Edward II, his lover and their small band of followers.

Hons And Rebels By Jessica Mitford

This play may sound bleak and uncompromising, but in general it is incredibly—dare I say it—entertaining. ‘Tarantino-esque’ as my friend described, is a very apt comparison. It’s the type of plot that Polanski or Ford Coppola would relish dipping their director toes into, making it an incredibly modern play to consume—at least the play as it is in the hands of director and Sport For Jove’s co-Artistic Director, Terry Karabelas. This acute sense of modernity is also reflected in Marlowe’s language, blank verse for the most part, but with some metaphysical metaphors that would delight Donne for example—but nothing too ponderous or flowery. No prolonged exposition, or soliloquies to be found in this play. In its place, gruesome, fast-paced violence and bleakly funny, heavily suggestive dialogue in its place. Arguably this leads to less fully drawn characters, with none of the psychological acuity of Hamlet, for example. Yet in Edward II, you do see the same shades, the same small flourishes of dramatic vividness that Shakespeare would later become so famous for. In the same way, the complexity with which the characters are drawn—in the sense that every single one of these characters are seemingly teetering the divide between the monstrous and monstrously sympathetic, makes Edward II a much richer, more varied work than meets the eye.

Much of this freshness is created by Karabelas’ cinematic, dramatically buoyant production. In this production, Karabelas creates a world that gives a definite sense of scope and history, despite limited resources and one of the smallest professional theatres in Sydney. Wonderful visual and audio touches abound. I particularly loved the sound design by David Stalley. The bombastic, ironic fanfare at Edward’s coronation, the delicate notes of Debussy’s Clair de Lune—a counterpoint to the dangerous hedonism of Galveston and Edward II’s lovemaking— and the gloomy choral pieces during interstitial parts of the play, give a great sense of urgency and tragedy to the general mood. This is amplified by the lovely bits of lighting by Ross Graham—where Carravaggio chiaroscuro abound—and the simple yet effective costume work by Melanie Liertz.

In terms of performance, Sport For Jove’s production is a wonderful ensemble piece in which every actor makes an impression. Most vivid include Julian Garner as Edward II—the tactless yet devoted regent. Last I saw of Garner he played John Proctor in Sport for Jove’s production of The Crucible, a role that he performed with with needlepoint intensity. It is a fierceness that he also brings unsparingly to Edward II. As his lover, Galveston—the Helennic character of the piece—is played by wonderfully by Michael Whalley who evinces a rather Eroll Flynnesque air. In a wonderful piece of dual casting, Whalley also plays Lightborn (an Anglo play on the name Lucifer), the man who ultimately steals Edward II’s last, careworn breath. Figuratively and literally, in Whalley’s hands, the act of assassination is a form of sensual embrace. Lightborn kills Edward II in the most intimate—and most disgusting way—possible, giving a new gruesome meaning to the phrase “la petite mort”. Another nice touch of referential casting comes in the form of Georgia Adamson, who played Elizabeth Proctor last alongside Julian Garner’s John Proctor and who appears again as Garner’s spouse in the character of Queen Isabella. The only character to be dressed in a colour amidst a canvas of monochrome—in her case, a rich scarlet—Isabella’s presence reminds me nothing so much as Margot of Valois and her bloody, tragic fate. Adding richness to the scenes are Belinda Hoare as the noblewoman Warwick and Angela Bauer as the Princess of Kent. Both women play roles initially written for men, yet their presence shapes relationships and transmutes the work for the better. It is exactly the sort of directorial decision which so typifies Karabelas’ and by extent, Sport for Jove’s intelligent, deeply imaginative readings of well-trod classics.

How exactly did this exciting theatre company create a production as darkly wonderful as any good Coen Brothers’ film—I’m not exactly sure—but I’m counting the days, hours and minutes until their next, highly-anticipated offering.

Edward II plays at the Seymour Centre until October 17th.

Tickets here: http://www.sportforjove.com.au/theatre-play/edward-ii